Philip Laurie and the Second World War at Greenwich Park

Thanks to the wartime diaries of one man, we have a remarkable record of life in Greenwich Park during the Second World War.

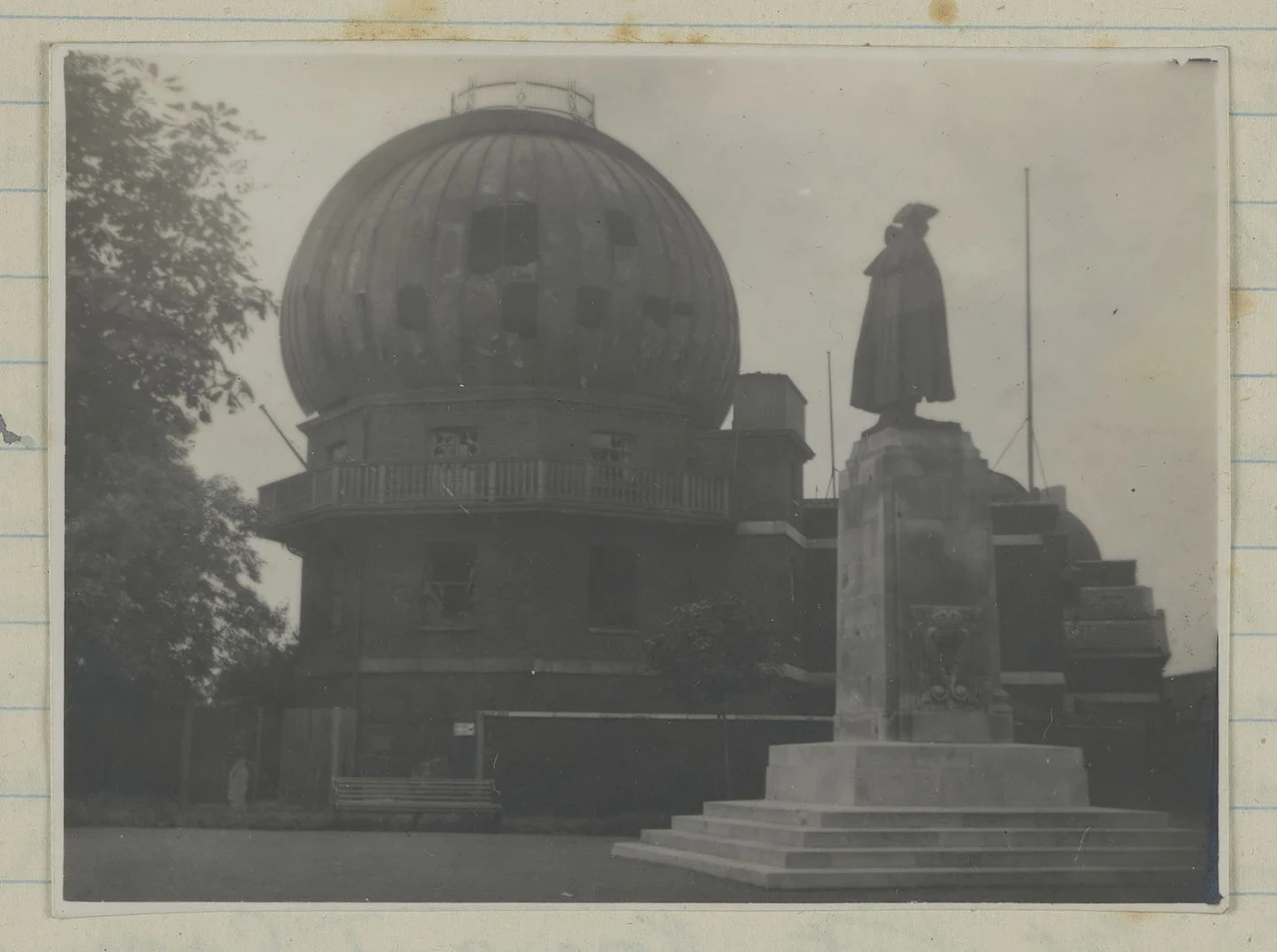

Philip Laurie (1913-1982) lived and worked at the Royal Observatory during the Second World War and his diaries from that time vividly record its impact on Greenwich Park.

Filling two notebooks, Laurie’s wry and forthright reminiscences describe falling bombs, park patrols and uncomfortable nights spent in air raid shelters.

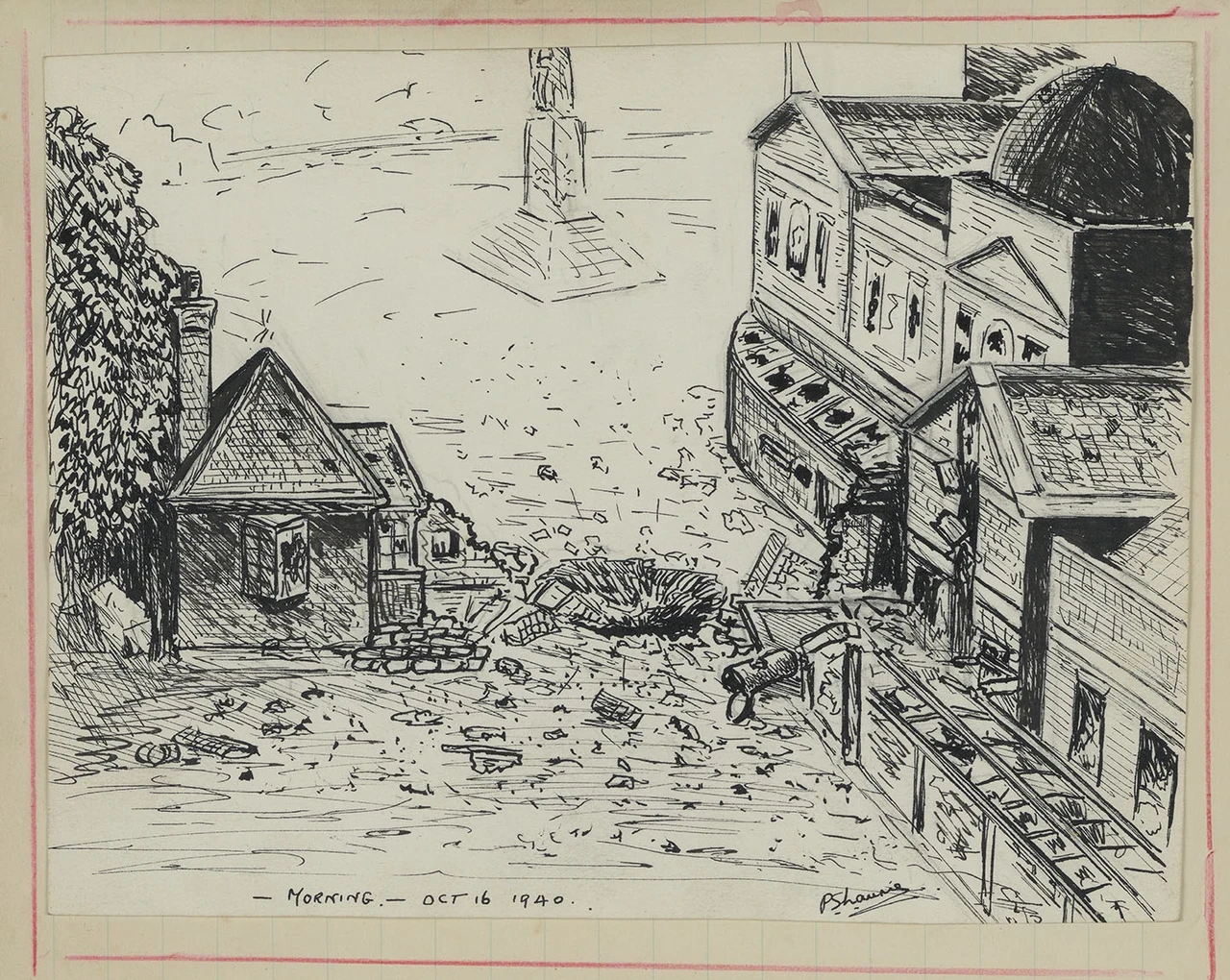

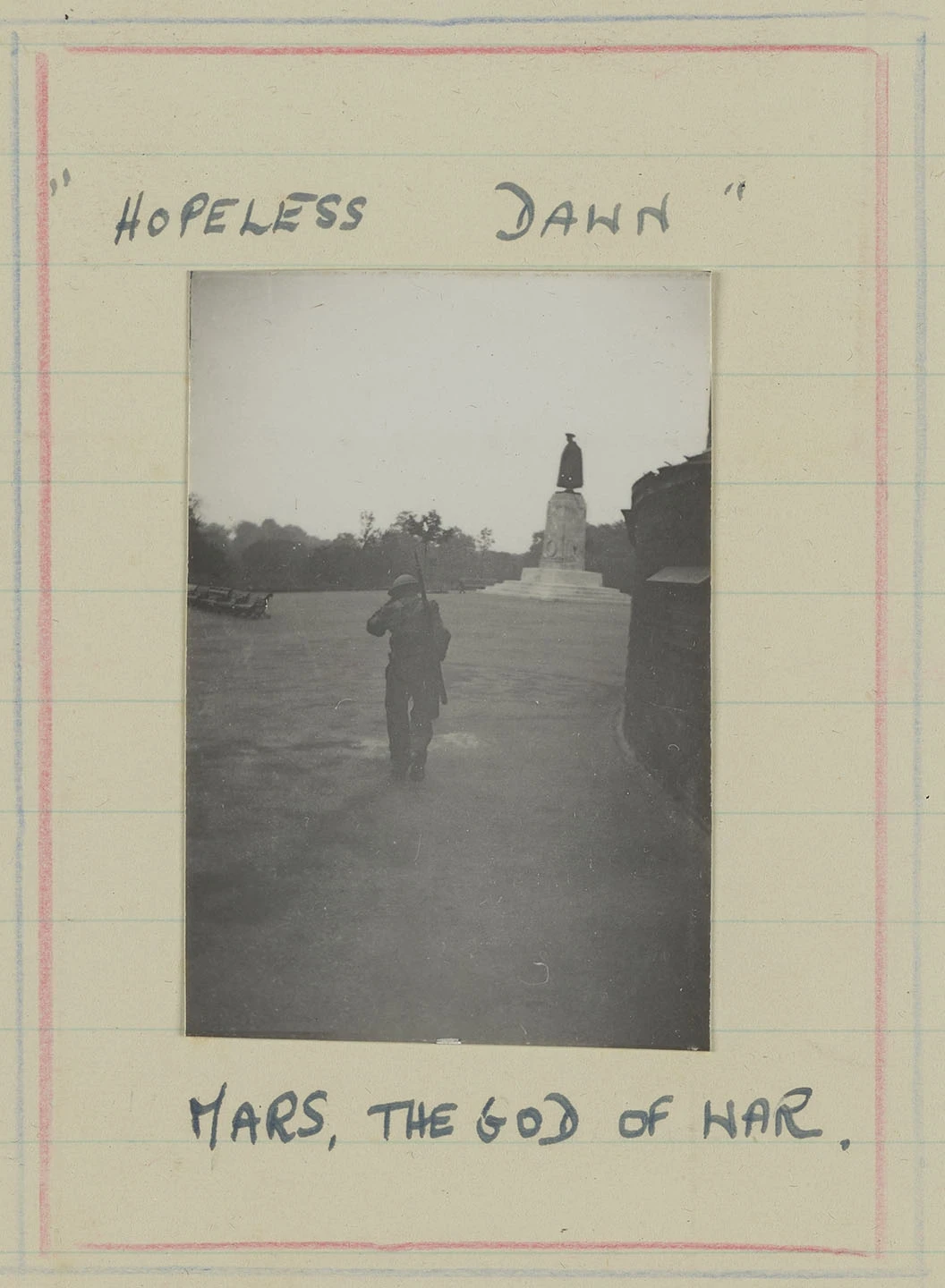

These recollections are illustrated with a series of extraordinary photographs and drawings capturing daily life in the park in wartime. All the images here are from Laurie’s notebooks and reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Who was Philip Laurie?

Born in Birkenhead in 1913, Philip Laurie was educated at Eltham College in London. After a succession of short-term jobs, he joined the Royal Observatory in 1935 as a ‘Temporary Computer’. This job title seems unusual today, but it meant that Laurie was tasked with processing complex observational data.

He was working in the Heliographic Department as one of a small group of people responsible for taking two photographs of the Sun each day to maintain the continuous record of solar photographs that had begun in the early 1870s. Laurie and his colleagues took the exposures, developed the plates in the dark room and then measured the position and size of sunspots using a solar plate micrometer.

When Britain declared war on Germany, Laurie was working at the Observatory. He recorded his experience of the rush of activity as staff scrambled to prepare for enemy attacks.

Preparing for war

Laurie’s diaries record that – in their own free time – staff placed sandbags around the Observatory buildings to protect them from bomb damage. The sand, he noted, had been sourced from the dockyard nearby. Laurie recalled that:

‘The full beauty of this occupation was not realised until the spring, when the bluebells growing out of the sandbags rivalled the Horticultural Society’s show.’

In September 1940, the majority of Observatory operations were moved to Abinger in Surrey, out of harm’s way. Laurie, however, remained in Greenwich Park. His work monitoring the Sun was important to the war effort because large sunspots and eruptions from the Sun could trigger disturbances in the Earth’s magnetic field that could in turn could disrupt short-wave radio signals.

Joining forces

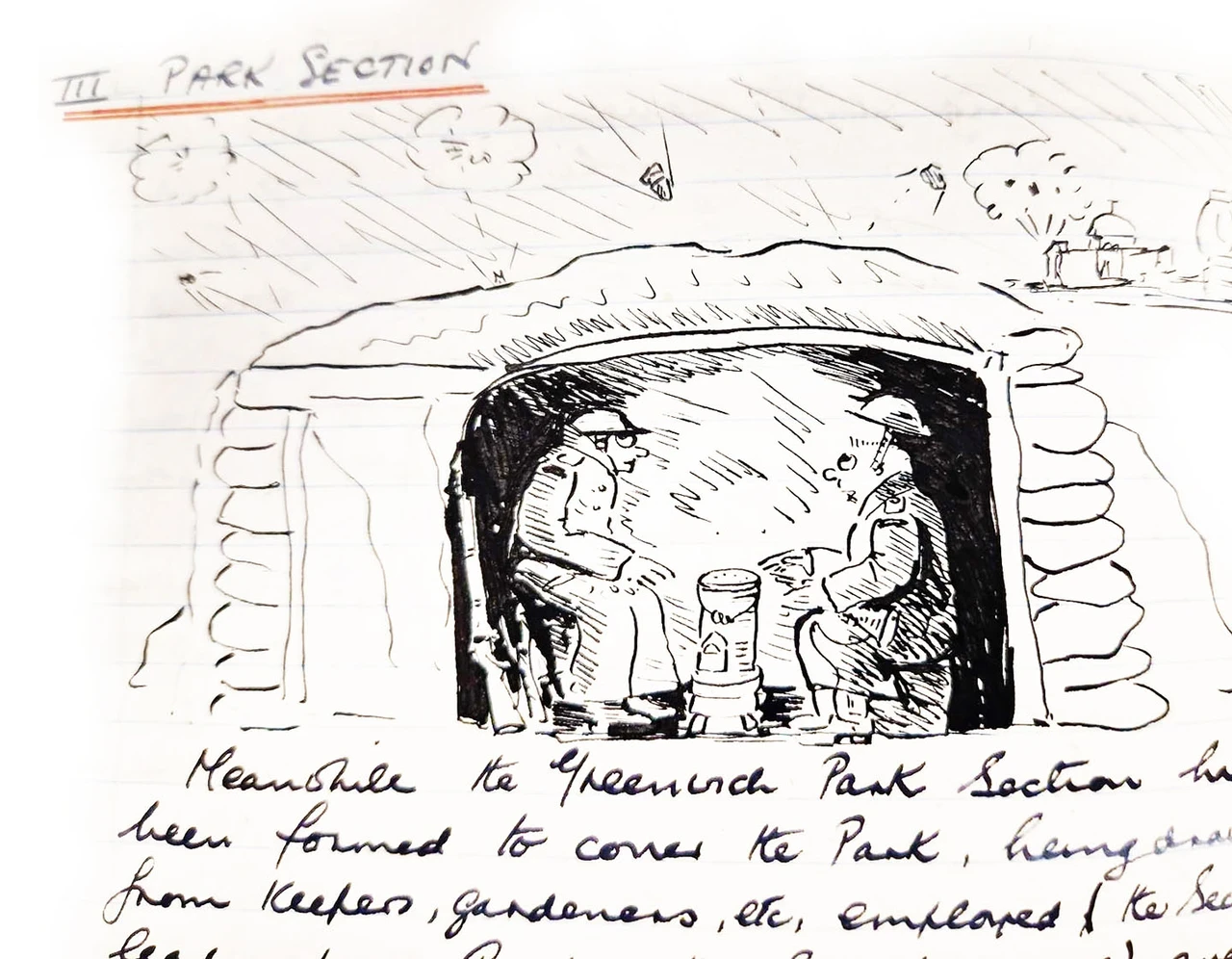

In Greenwich Park, staff had formed their own defence unit – the Greenwich Park Section. Amongst its members were gardeners and park-keepers, led by Greenwich Park Superintendent, Austin. In 1940, Laurie joined the unit along with other Observatory staff who had stayed behind in Greenwich.

The Greenwich Park Section performed drills in the park and trained in the area known as The Wilderness – close to where an anti-aircraft battery was located at this time. The Section also guarded the park’s air raid shelters and kept watch for doodlebug bombs. These were especially terrifying as they created a buzz which cut out when the bomb ran out of petrol – they would then fall to the ground and explode. Approximately 10,000 were fired at England – 2,419 reached London killing about 6,184 people and injuring 17,981.

The Observatory Garden

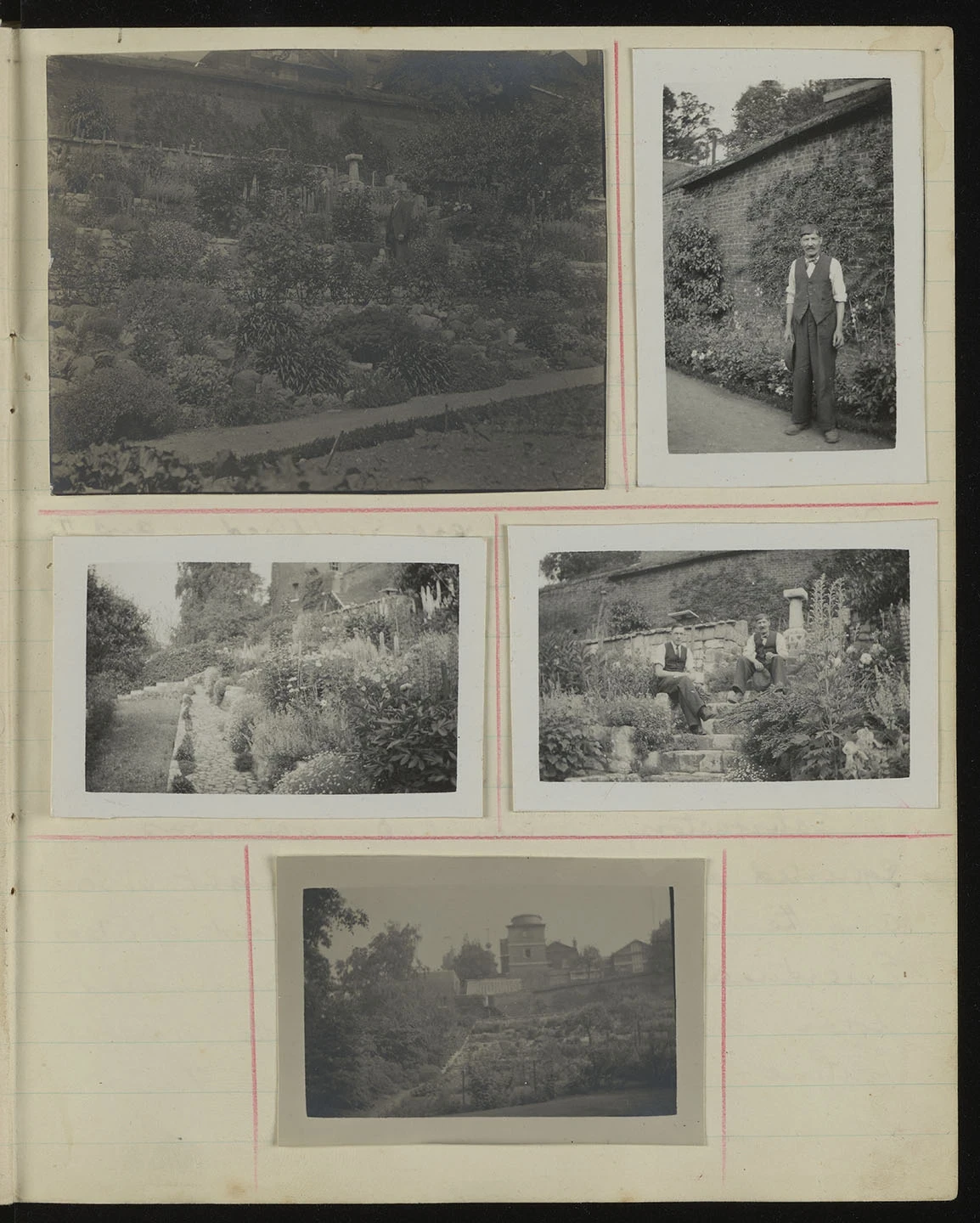

Regular visitors to Greenwich Park will be familiar with the Observatory Garden – a quiet area tucked beneath the Observatory buildings. Once a private garden for Observatory staff, it is now part of Greenwich Park.

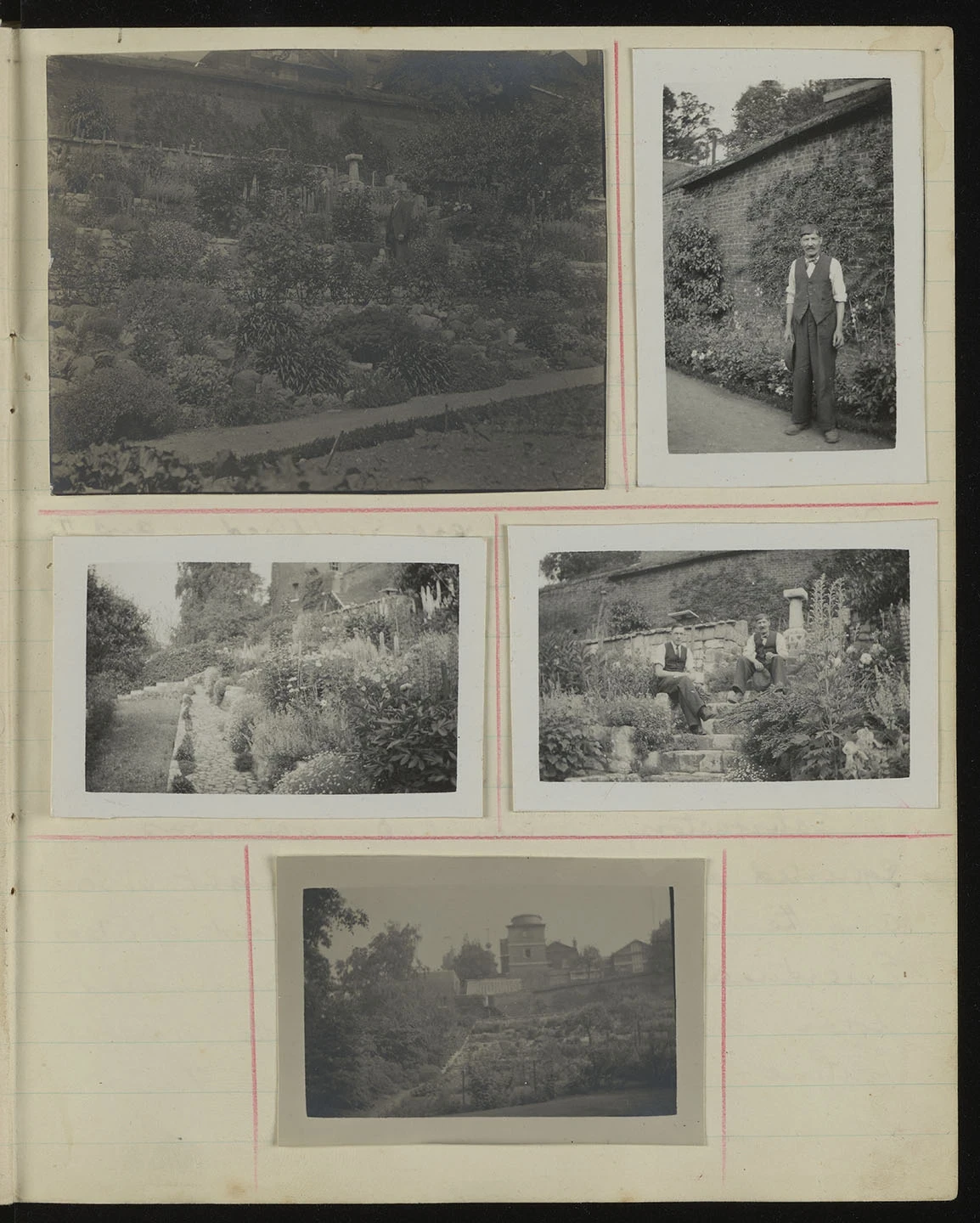

During the war, when the area still belonged to the Observatory, this is where gardeners named Thurlow and Carter grew produce for staff. The fruit and vegetables they grew were highly sought-after in a time of shortages and rationing.

Laurie recalls the work of these gardeners, noting that their produce was often a target for thieves:

‘Carter, whose effort was mainly directed to peach and grape production, (and other such war essentials) spent his spare time erecting barricades round the garden, including two notices whimsically announcing “PRIVATE”, and wondering where the export produce was going to. This problem remained insoluble in spite of all precautions as suspects were too numerous.’

The Blitz

Unsurprisingly, Laurie had much to say about the Blitz. Greenwich was heavily bombed during this period, due to the docks and factories along the banks of the Thames.

Laurie reflects:

‘Overhead, in the daytime, the Battle of Britain was being won though few realized its importance. Bombs now scarred many neighbouring districts including some in the Park, but when sirens went at 4.56 pm on Saturday, Sept. 7th, no one took it to be anything other than one of the now commonplace alerts. A quarter of an hour later they knew better and the Luftwaffe was over London. After an hour they went, leaving fires everywhere and black smoke pouring thousands of feet into the sky. Two hours later they came back.’

Laurie could only watch as the bombs fell on Greenwich:

‘There was nothing much to be done about things at the [Royal Observatory] except keep a weather eye on incendiaries which fell nearby on several occasions. H.E.s [high explosive bombs] came down thick and fast and the Park began to assume a rather pock-marked aspect.’

The Observatory is hit

Laurie recalls at least two occasions when the Observatory was hit directly. At 10.20pm on 15 October 1940, a bomb fell on the building’s main gate, which Laurie said removed the gate ‘and the neighbouring sections of wall’, fragments of which landed on the roof.

Laurie goes onto explain that ‘glass fell in or out and a nice hole appeared where all the house services met.’ This hole in the wall revealed a scene that was particularly embarrassing for a colleague named Hogan – Laurie says ‘Hogan’s underpants, drying before the fire, suffered severely’!

The Wolfe statue outside the Observatory – visible in some of Laurie’s photos and sketches – still bears the scars of bomb damage from the Second World War, and this may have occurred during the raid he describes here.

‘Thousands of incendiaries’

Looking back at the bombing raids on London, Laurie reflected on the extraordinary number of bombs that fell on Greenwich Park. He said:

In the raids of 1940-41 the Park had received as its share some 98 HEs [high explosives] and some thousands of incendiaries, so to this total could be now added one doodle 50 yds from the original post and another in the Wilderness near the Flower Gardens. Another half dozen landed close to, but just outside, the Park Wall.

The next attraction arranged by Hitler was the V2, several of which fell in the area (the tail ends of two falling in the Park.)

After the war

After the war, in 1946, Laurie was given a permanent post at the Observatory. By 1960 he had become a Senior Experimental Officer, eventually retiring as Head of the Solar Department. In 1975 he was awarded an MBE in recognition for his solar work, but also for his role in managing and improving the Observatory archives.

Today Laurie’s invaluable wartime memoirs form part of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archive, now held at Cambridge University Library.

With thanks

With thanks to Dr. Emma Saunders, Archivist of the Royal Greenwich Observatory Archives at Cambridge University Library and Dr. Louise Devoy, Senior Curator at the Royal Observatory, Royal Museums Greenwich.

Related Articles

-

Read

ReadGeneral Wolfe at Greenwich Park

The statue at the top of the Grand Ascent was a gift from the Canadian people in 1930. But who was the General? And what was his connection to the park?

-

Read

ReadA digital exhibition about Hori Tribe

A digital exhibition about Hori Tribe, a propagator at Greenwich Park, who left to fight in the First World War.

-

Read

ReadUnearthing an air raid shelter in Greenwich Park

As part of our Greenwich Park Revealed project to restore and protect the park we delivered a community dig to find out more about a lost air raid shelter.