The Royal Parks in Literature

“To escape is the greatest of pleasures,” Virginia Woolf wrote in her essay ‘Street Haunting: A London Adventure’ (1930). She described how “[walking] alone in London is the greatest rest”, offering the kind of imaginative freedom that only solitariness affords: the opportunity to look beyond oneself and, in the striking vignettes of people and places, see into the lives of others. There’s a lot to be said for taking a mental journey through the landscapes we love with the help of a good book or few…

Virginia Woolf

An integral part of Woolf’s London were the Royal Parks. As a child she walked twice daily in Kensington Gardens with her father, the critic and author Leslie Stephen. The family lived at 22 Hyde Park Gate in Kensington, just opposite the largest expanse of greenery in the city. Though she often found the repetitiveness of these walks tedious, it did encourage Virginia and her siblings to make up “long long stories” to pass the time (‘A Sketch of the Past’, 1939). With her sister Vanessa she even produced a family newspaper, ‘The Hyde Park Gate News’, which provides some wonderfully satirical insights into their household and the ritual visits to Kensington Gardens – from playing hide and seek to avoiding the woman who paraded there every day in a dirty dressing gown. What in childhood was a chore became for the adult writer a lasting source of comfort, respite and inspiration; indeed, she wrote in her diary that...

“the greatest happiness in the world is walking through Regent’s Park…making up phrases” (6 June 1935).

Image: portrait of Virginia Woolf by George Charles Beresford, 1902 © National Portrait Gallery

Mrs Dalloway

Where strangers appeared “hideous” pouring along Oxford Street or “squalid sitting opposite each other staring in the Tube” (‘Street Haunting’), London’s most famous parks transformed them into thoughtful human beings capable of sensitive feeling and reflection. This included Woolf’s own characters: most famously, Mrs. Dalloway goes on a jaunt for flowers that takes her through central London and St. James’s Park, embarking on a heady steam of consciousness in which past and present turmoil tangles her mind. A memory of rejecting her one-time love “in the little garden by the fountain” haunts her still. Similarly, the teeming leaves and trees in The Regent’s Park allow the imagination of a traumatised war veteran to run riot; there he crosses paths with a teenager newly arrived in London who...

“should she be very old…would still remember…how she had walked through Regent's Park on a fine summer's morning fifty years ago”.

Charles Dickens

Woolf was just one of many writers who sought out the Royal Parks to stir their creativity. For over a decade between 1839 and 1851 Charles Dickens lived opposite The Regent’s Park, writing The Old Curiosity Shop, Barnaby Rudge, Martin Chuzzlewit, Dombey and Son and David Copperfield in a now-demolished house. From “delightful” Greenwich Park in Our Mutual Friend to the “raw, damp dark” St. James’s Park in Martin Chuzzlewit, the parks provide the backdrop for several poignant, comic and dramatic interludes in Dickens’ work.

Dickens was particularly drawn to “the park, par excellence” Hyde Park for its historic associations with the public hangings that took place at the nearby Tyburn Tree from the medieval period to the 18th century. The site, which is now memorialised in the park, features recurrently as a terrifying spectre of punishment and retribution in Barnaby Rudge. Several months before he died Dickens rented a house at Hyde Park Gate (No. 5); he would frequently roam the park while working on his final unfinished novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood.

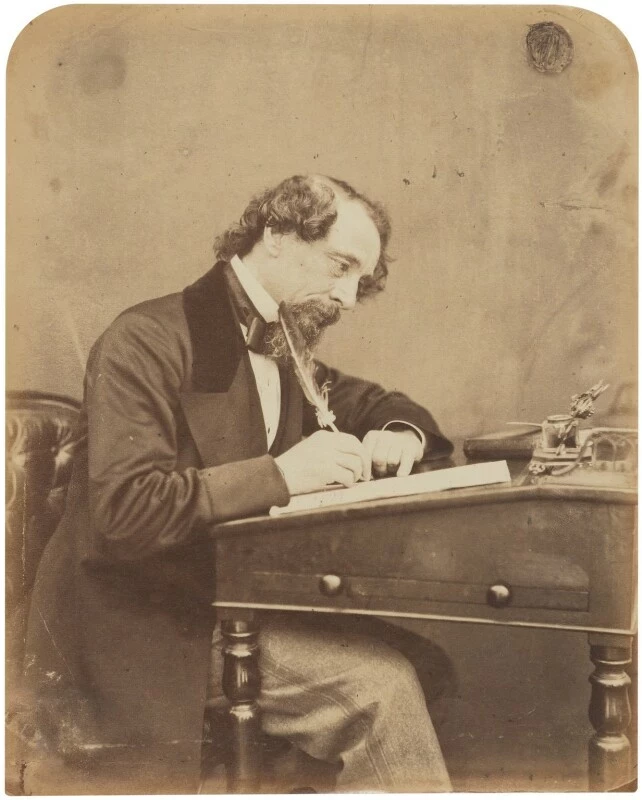

Image: Charles Dickens by Herbert Watkins, 1858 © National Portrait Gallery

Wandering minds

Meanwhile, that other great bastion of the Victorian novel, Mary Anne Evans, began writing her first novel Scenes from Clerical Life shortly after moving to Richmond in 1855. It was also while living here that she acquired the famous nom de plume, George Eliot. She enjoyed regular walks in Richmond Park and was constantly struck by its “delicious” views – “the blue mist…that seemed to hang like a veil before the sober brownish-yellow of the distant elms” (Journal, 28 November 1857). Interestingly, Woolf too sought refuge in Richmond for a time and took her dog Max for walks in the park; it was while living here that she founded the Hogarth Press with her husband, which published works by their literary circle, known as the ‘Bloomsbury Group’.

By seeking recreation, relaxation and stimulation in the Royal Parks, these great authors were following closely in the footsteps of one of the very first people to write about the significance of the parks in public life. Samuel Pepys’ fascinating diary, spanning the 1660s, recounts momentous events from the Great Plague to the Great Fire of London; it also describes Pepys’ habitual walks in St. James’s Park, where he shared confidences with friends, spent precious time with his wife, and even entertained himself by playing the flageolet (a type of flute – as if you need to ask!).

Peter Pan

Yet the Parks have not always been perceived by literary minds as down-to-earth places for everyday activities. After all, perhaps their most famous resident is Peter Pan, the boy who wouldn’t grow up. Author and playwright J.M. Barrie’s ultimate flight of fancy, Peter first appeared in a novel called The Little White Bird (1902) as a “Betwixt-and-Between” boy-bird who finds himself stranded in Kensington Gardens and raised by the magical creatures who live there.

Barrie lived just across from Kensington Gardens at 100 Bayswater Road, and is thought to have been inspired by his friendship with the five Llewelyn Davies boys, who he met by chance in the park. It is said that Barrie is responsible for secretly installing the enchanting bronze Peter Pan statue that retains pride of place in the park today; it marks the spot where Peter Pan landed as a baby when he flew out of his nursery window. It is fitting the statue was erected under the cover of darkness after “Lock-Out Time”, when the fairy folk are able to emerge at last. Barrie even reimagined the hidden pet cemetery on the border of Hyde Park, with its miniature headstones, as the graves of children who had been left behind in Kensington Gardens after closing time.

The War of the Worlds

But there have been other fantastical forays into the Parks that were not so innocent. In H.G. Wells’ apocalyptic masterpiece The War of the Worlds (1898), London is the epicentre of a deadly Martian invasion by “boilers in suits’ a hundred feet high”. Devastating destruction extends to the suburbs, where “the blazing trees along the slopes of Richmond Park…threw their light upon a network of black smoke…extending as far as the eye could reach”.

Returning to the wreckage of the deserted city centre, our hero is drawn by the aliens’ “superhuman…desolating” wails to Primrose Hill. This is where the novel’s famous conclusion takes place amid “the tattered red shreds of flesh that dripped down upon the overturned seats on the summit”. Though wildly different in tone and scale, Wells’ dark tale in which the park is a place of transformation and ultimately redemption is echoed in the kinds of emotional upheaval Woolf depicts when characters are given the (green) space to think.

Image: Portrait of H.G. Wells, 12 April 1911 © National Portrait Gallery

Shared space

The Royal Parks have also been configured as sites of modern social commentary. George Orwell enthused about regularly visiting Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park, Britain’s home of free speech. Calling the public meetings “one of the minor wonders of the world”, he took the opportunity to speak himself and also listed the diversity of views he had seen represented: “Indian nationalists, Temperance reformers, Communists, Trotskyists…Freethinkers, vegetarians, Mormons, the Salvation Army, the Church Army, and a large variety of plain lunatics” – all of whom received “a fairly good-humoured hearing from the crowd” (‘Freedom of the Park’, 7 December 1945).

The idea of Hyde Park as a communal gathering-place where vastly different people come together – both intimately and uncomfortably – was seized on by Trinidadian author Samuel Selvon in his 1956 novel The Lonely Londoners. This was one of the first works to explore challenges faced by the post-WWII ‘Windrush generation’ of Afro-Caribbean immigrants to the UK.

Image: Speaker's Corner in 1947 via Wikimedia Commons

The vivid variety of life in The Royal Parks was most recently encapsulated in a series of short prose pieces specially commissioned by the charity. Park Stories (2009) brings together eight notable contemporary writers, each providing original and insightful takes on the green spaces at the heart of the capital.

Literature has the power to bring the outside indoors and to make one little room an everywhere, so we hope this literary tour of the Royal Parks has given you some ideas for where to start.

And who knows, the next time you’re getting your daily dose of exercise in one of our parks it may just spark some creativity of your own…

Related Articles

-

Read

ReadShrine of Youth: The Peter Pan Statue, Kensington Gardens

The Royal Parks are bursting with literary history. Perhaps the most famous fictional resident of the parks is Peter Pan – the boy who wouldn’t grow up.

-

Read

ReadRemembering Ignatius Sancho

Ignatius Sancho was a writer, composer and abolitionist who lived on the edge of Greenwich Park, and became the first black person to vote in Britain.

-

Read

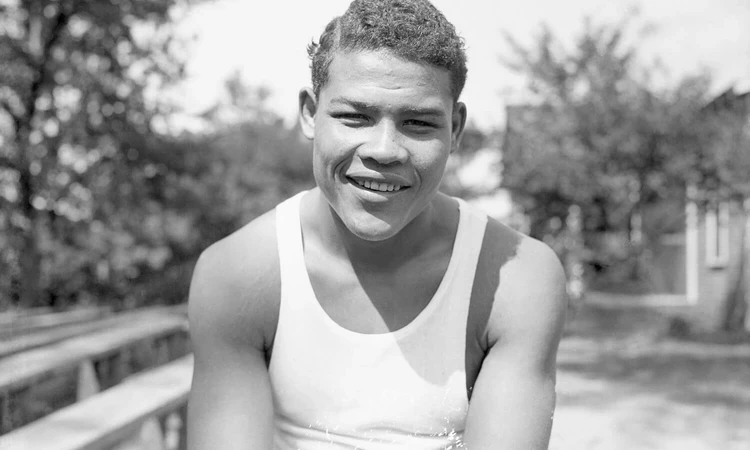

ReadJoe Louis at Bushy Park

Joe Louis is remembered as one of the first black sportsmen to transcend the colour barrier, and in WW2 he made a special appearance at Bushy Park.