Trees through time at Greenwich Park

The trees of Greenwich Park have had a lot to contend with over the years.

From weather and war to squirrels and stargazers; all of these factors have had an impact on the treescape.

Managing this impact on the trees has long been an important job for those who look after the park. Surviving records from the 1800s give us a glimpse at the sorts of issues that park keepers had to attend to. In 1817, a survey was taken of trees in the Park. It found that 475 needed to be felled but suggested that 1,000 were planted in their place.

These new trees included English and wych elm, Spanish and horse chestnut, beech, Scots and lark firs. The surveyor, Edward Kent, noted that ‘The wych elm grows remarkably well in [the] park’.

Later, in 1850, Park Superintendent John Gibson wrote a report on the state of trees in the Park, noting that they ‘assume various degrees of luxuriance and decay’.

Gibson explained that many trees making up the Park’s long avenues were beginning to deteriorate. He recommended that, through ‘timely’ planting, these avenues should be replaced with something more in keeping with the ‘style and taste of the present day’. This, he suggested, would open up views and compliment the landscape’s ‘beautiful undulations’.

Despite Gibson’s ideas, the avenues laid out in the seventeenth century are still a notable feature of Greenwich Park. Several Sweet Chestnut trees planted in the 1660s remain today. These veteran trees contribute a huge amount to the beauty of the park.

Throughout the nineteenth century, many trees in the park were lost due to severe storms. When one storm struck in 1868, local artist John Gilbert was on hand to record the damage.

His watercolour capturing the aftermath of the storm is now in the collection of the Royal Academy. In this picture, we can see a hive of workers sawing the fallen trunk and removing branches in a horse-drawn cart. Meanwhile, curious visitors gawp at the fallen tree and its immense roots.

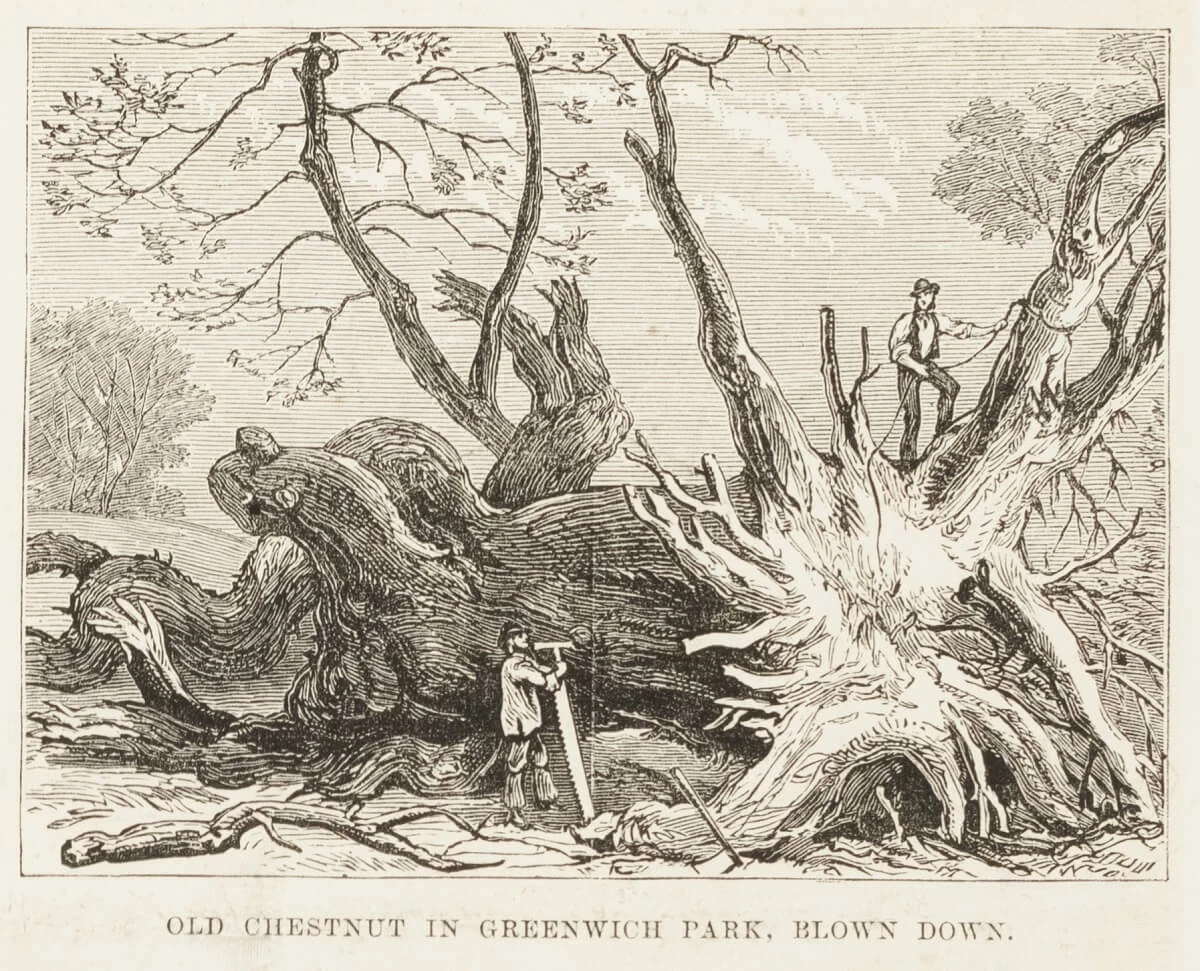

One of the worst storms to hit Greenwich Park in the nineteenth century occurred in October 1881.

‘A storm of wind, seldom equalled in violence and long continuance’ is how the Illustrated London News described it, sharing images of the destruction wrought across the capital. In one, a chestnut tree in Greenwich Park is shown torn up from the ground. A man stands on top, dwarfed by the tree’s exposed roots.

Storms have shaped the park’s landscape in the 20th century, too. In 1987 England was lashed by a hurricane-force storm. It is thought that around 15 million trees were lost across the country.

4,500 trees were lost across the Royal Parks - all of which were forced to close for several weeks while the damage was cleaned up.

Wildlife

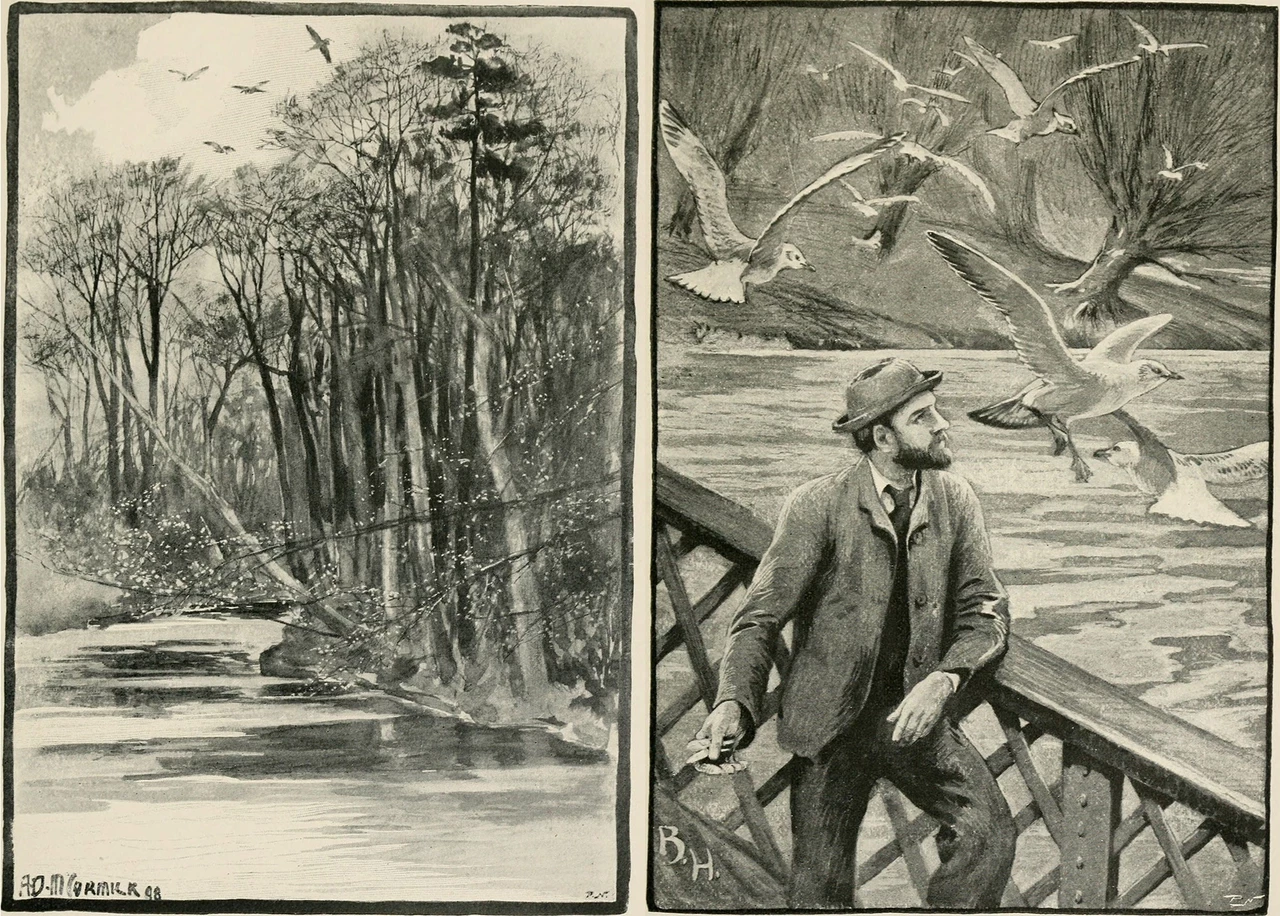

Trees are vitally important to the wildlife of Greenwich Park. One Victorian who recognised this was the eminent naturalist W. H. Hudson, who wrote many books about birds.

In 1898, Hudson published Birds in London, a volume that described avian activity in the metropolis.

In this volume, Hudson describes the state of trees in Greenwich Park:

[T]here are not in England such melancholy looking trees as those of Greenwich. You cannot get away from their said mutilated condition.

Hudson goes on to link these unhealthy trees to the disappearance of birds from the park, noting that jackdaws and owls are no longer seen there.

Hudson would be happy to know that things have much improved. More than 30 species of bird are known to breed in Greenwich Park today, including nuthatches, goldcrests, chiffchaffs, blackcaps, coal tits, ring-necked parakeets, song thrushes and stock doves.

Today, many squirrels enjoy the trees of Greenwich Park. Though they might be cute, these animals are actually responsible for quite a lot of damage!

The Park at War

Visitors admiring the mature horse chestnut trees as they stroll along Blackheath Avenue today may be surprised to learn that back in the 1940s - within living memory - these magnificent trees were no more than young saplings.

The whole avenue was replanted around 70 years ago. In the photographs above, you can see the avenue of mature trees in 1924 and the new saplings growing in 1948. Unfortunately, park records from this period do not survive, so we cannot be sure why this happened – though war damage might have had something to do with it.

The area surrounding Greenwich Park has been described as ‘one of the hardest-hit areas of London during the air raids’ and records show that at least several bombs fell around Blackheath Avenue during the Second World War.

The scars of this period are still visible – look at the damage on the plinth of the Wolfe statue, that stands at the end of Blackheath Avenue.

It was not just bombs that altered the treescape of the park during the Second World War. Anti-aircraft guns were set up in the Flower Garden; in order to widen the field of fire, some of the trees were cut down.

Seeing Stars

Sometimes the trees of Greenwich Park have been altered for more positive reasons. The Royal Observatory opened in the park in 1676. Over the centuries, astronomers have used telescopes and other scientific equipment to explore the heavens. Sometimes, though, trees have got in their way!

In 1836, a First Assistant at the Observatory wrote to Astronomer Royal George Airy to report that a colleague ‘cannot observe several stars very low in the South on account of the trees that which are in the way, especially of Jones Circle.’ The Assistant later reports to Airy that he has put marks on the offending trees, ready for the gardener to break off branches once Airy has authorised their removal.

Later on, in 1862, Airy wrote to carpenter John Green asking him bend the trees aside to make way for the trials of some new telescopes!

Related Articles

-

Read

ReadQueen Elizabeth Oak in Greenwich Park

Greenwich Park boasts thousands of trees, but Queen Elizabeth’s Oak is easily the most famous.

-

Read

ReadGreenwich Park in Art

For centuries, artists have flocked to Greenwich Park armed with sketchbooks, palettes and canvases.

-

Read

ReadFamous Artists at Greenwich Park

Among the thousands of artists who have found inspiration in Greenwich Park are three of the most well-known figures in Western art…