The suffragettes in Hyde Park

Today, Hyde Park is a place where you can slow the pace, reconnect with nature, and enjoy the peace. But in the past, Hyde Park was anything but peaceful. It was a hotbed of political activity – and one of the key sites for the Suffragette movement.

Speakers’ Corner and the Suffragettes

Hyde Park is the people’s park. And Speakers’ Corner, tucked in the north east corner of the park, is the people’s stage. Since the 1800s, anybody can speak, on any subject that they feel strongly about. It’s the place to rally people to your cause, speak your mind, or peacefully protest.

Speakers’ Corner has been the forum for trade unionists, animal rights campaigners, anti-war protestors and, more recently, supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement. Famous people including Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Bianca Jagger, have all drawn crowds at Speakers’ Corner with impassioned speeches.

But the most famous group to meet and speak at Speakers’ Corner, was the Suffragettes. ‘Suffrage’ is the old word for ‘the vote’ – and Hyde Park was the birthplace of the Suffragettes courageous campaign to win women the vote.

What was the Suffragette Movement?

The Suffragettes are probably the best known campaigners for women’s rights, especially voting rights. But the history of feminist thought in Britain stretches back much further.

As early as 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft published A Vindication of the Rights of Women. This trailblazing feminist manifesto argued that women should have equal opportunities in education, work and politics. Back then, it was radical, even dangerous to air these views.

During the 1800s, many who shared Wollstonecraft’s views campaigned for women’s ‘suffrage’, or the right to vote. The first petition calling for such rights was presented to Parliament in 1832.

By 1897, support was growing in many communities, and the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was formed to try to unite the different groups. But by the end of the 19th century, they’d made almost no progress. And the women of Britain were running out of patience.

1905 – the turning point

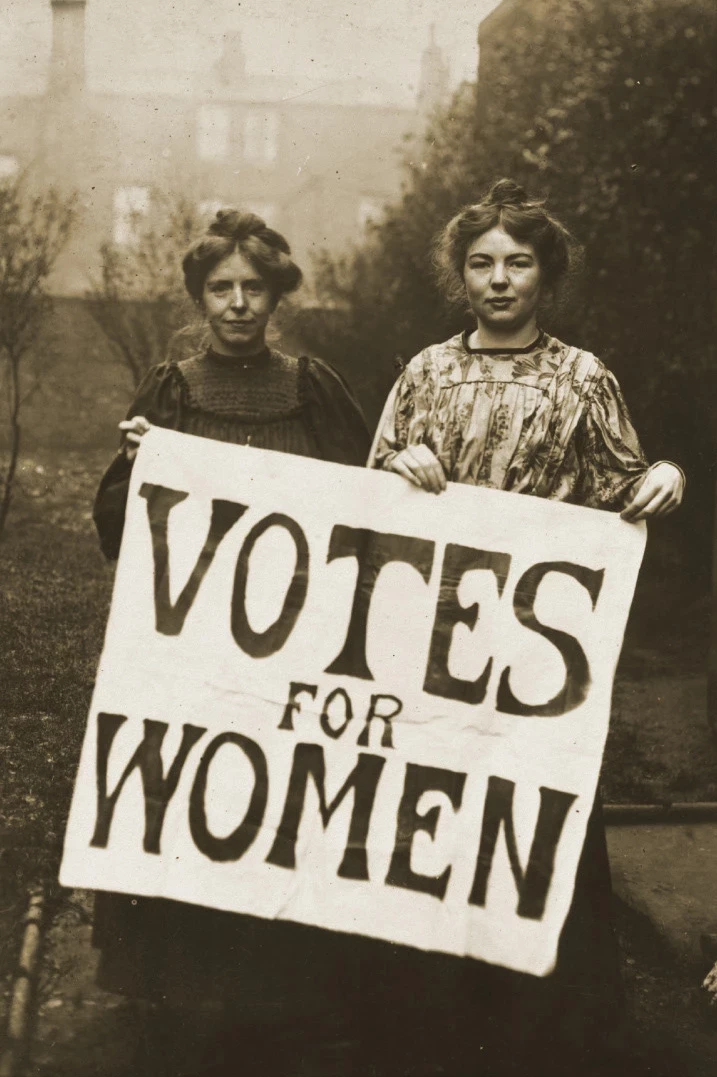

On 13th October 1905, two bold young women – Christabel Pankhurst and Annie Kenney – interrupted a political meeting in Manchester. They demanded to know whether any of the speakers – one of whom was a young politician named Winston Churchill – would grant women the vote? And then they unrolled a banner that read ‘‘Votes for Women’.

Scuffles broke out, and Annie and Christabel were arrested. It was the start of the Suffragette campaign.

The Suffragettes were led by the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and believed that deeds, not words, would win the fight. The WSPU was led by Emmeline Pankhurst, Christabel's mother, probably the best known of all the Suffragettes.

The Suffragettes organised rallies up and down the country, raised funds, recruited new members and published their own newspaper. And as time went on, their tactics became more extreme.

Smashed windows, hunger strikes, and arson

Frustrated by the lack of political support from the establishment, the Suffragettes grew more active. Windows were smashed, the contents of post offices were burned, and some Suffragettes were even involved in bombing campaigns.

Scores were arrested for these protests. Behind bars, many Suffragettes went on hunger strike to continue their protest. The government responded with a policy of force feeding; a procedure that outraged many.

Eventually, the government agreed to release Suffragette hunger strikers if they became dangerously ill. But it was only a respite. The Suffragettes had to continue their prison sentences as soon as they were strong enough. Many Suffragettes simply refused to return – and this policy was nicknamed ‘the Cat and Mouse Act’. It was a case of ‘Catch me if you can’.

Not everyone signed up to this style of militant protest. At the same time, the long-standing NUWSS, led by Millicent Fawcett, promoted more peaceful means of protest. These women became known as ‘Suffragists’, in contrast to the more radical ‘Suffragettes’. They were united in one thing however – a woman’s right to vote.

Both groups would hold historic rallies in Hyde Park. The park would play a crucial role in the campaign to win women the vote.

Fighting for Women’s Suffrage at Hyde Park

Between 1906 and 1914, the Suffragettes could often be found at Hyde Park. It became a key site for their meetings, rallies and protests.

During the summer of 1906, the Suffragettes held a weekly meeting near to the Reformers’ Tree in Hyde Park. This well-known tree, close to Speakers’ Corner, gained its name in the 1860s when it became a meeting point for protests organised by the Reform League. Their goal was to get all adult men the right to vote.

But during one protest, tempers ran high, and the tree was set on fire. The charred stump became a notice board, and a rallying point for meetings and symbol of the people’s right to protest. It was here that the Suffragettes held many of their meetings.

Fiery speeches – the Pankhursts and the Park

In August 1906, the Globe newspaper ran a story with the headline ‘RELEASE OF WOMEN AGITATORS FROM PRISON BY MOTORCAR’. Suffragette Annie Kenney had been let out of Holloway Prison for yet another act of protest.

On her release, the Globe explained, Kenney would be one of the principal speakers at a ‘great mass meeting’ in Hyde Park: “The meeting, which is to be held under the Reformers Tree, will also be addressed by Miss Christabel Pankhurst.” Annie Kenney and Christabel Pankhurst were close friends and had been partners-in-crime since they’d heckled Churchill in Manchester.

The Edinburgh Evening News ran a report under the headline ‘SUFFRAGETTES IN HYDE PARK’. Around 1000 women had gathered to hear Kenney talk defiantly about her time in prison.

The atmosphere was electric. Christabel Pankhurst gave a barn-storming speech in which she ‘rejoiced’ that the Government recognised the Suffragettes as dangerous, declaring that women have more spirit than men. And she concluded: “Women, once they had got hold of anything, will not let it go.”

Women’s Sunday – a record-breaking rally

In June of 1908, Suffragettes from all over the country flooded into London on specially chartered trains. They were here for a ‘monster meeting’, called Women’s Sunday.

This record-breaking rally, attended by up to half a million women was, at the time, the largest protest to ever have taken place in Britain. It was held on a Sunday so that as many working-class women could attend as possible.

The women marched through London in seven carefully choregraphed processions. 30 bands played, and 3,000 standard bearers led the way, waving flags and banners emblazoned in green, white and violet – the colours of the Suffragettes.

‘The Day of the Great Shout’

By the time they reached Hyde Park, the demonstration had swelled to 300,000. 20 platforms had been erected, so the 100 speakers could be seen by the huge crowds. It was big, even by Hyde Park standards.

According to the newspaper report in the Lakes Herald: “The speakers were drawn from all sorts and conditions of women. Some were mothers of families, others were teachers, mill and factory workers, shop assistants, clerks, journalists, novelists, musicians, a playwright, a bachelor-of-law, a tailoress and a nurse.”

Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the WSPU, was at the top of the bill.

At the end of the rally, a bugle sounded from a platform. The chant went up: ‘Votes for Women! Votes for Women! Votes for Women!’. The newspaper report concluded:

“From thousands of throats the cry came, gathering in volume until it sounded like the roar of a football crowd when the home team scores a goal. Within a few minutes […] demonstration day – the day of the great shout – was over.”

Winning the right to vote

The Great Shout didn’t win the battle, but the tide was turning. The Suffragettes and Suffragists took to Hyde Park many more times before women finally won the vote in 1918. The Representation of the People Act, introduced that year, allowed women over 30 to vote if they met a property qualification.

It was not until the Equal Franchise Act was introduced in 1928 that all women aged over 21 were granted the same voting rights as men.

The Royal Parks and the Suffragettes

Hyde Park isn’t the only Royal Park with a Suffragette past. A statue of Emmeline Pankhurst stands in Victoria Tower Gardens, next to the Houses of Parliament. And Emmeline herself is buried in Brompton Cemetery . The the grave of Emmeline Pankhurst, is still an important shrine for women around the world.

Related Articles

-

Listen

ListenWomen in The Parks

In this episode, recorded for Women’s History Month, we look at some of the great women associated with the parks.

-

Read

ReadWomen of The Royal Parks

Women's History Month takes place each March, highlighting the contributions of women and their achievements.

-

Read

ReadThe Story of Alice Elizabeth Jarman

The story of one woman’s tragic murder – a glimpse into women’s lives, wartime London and the history of Kensington Gardens.