A Royal Landscape at Greenwich Park

In the 1660s, King Charles II (1639 – 1685) had Greenwich Park redesigned to an ambitious scheme known as ‘The Grand Plan’.

This bold vision introduced hundreds of trees to the park in a formal layout of avenues, creating a treescape that can still be enjoyed today…

Charles II at Greenwich

On 29th May 1660, Charles II returned to England. For nine years he had been living in exile on the continent, due to the tumultuous events of the English Civil War (1642-51). This bitter conflict had culminated in the execution of his father, King Charles I, and the abolition of the monarchy.

England’s new republican leader, ‘Lord Protector’ Oliver Cromwell, died in 1658. This set in motion a chain of events that ended with the restoration of the monarchy under new King, Charles II.

He would remain on the throne for some very eventful periods in British history, including the Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of London in 1666.

When he returned to England, Charles found that the capital’s royal palaces had been sold off or destroyed by Cromwell and his supporters. The only habitable palace was at Greenwich, so he turned his attention towards restoring it.

The surrounding park was an important part of the restoration of Greenwich Palace. Charles had been inspired by the grand gardens he enjoyed during his time in Europe and wanted to create something similar in London.

He knew just the right men for the job.

André Le Nôtre and the parterres

Le Nôtre was a celebrated landscape architect who worked for Louis XIV of France (1638 – 1715). He was responsible for designing the dazzling gardens at the French King’s Palace of Versailles.

Le Nôtre’s extravagant gardens at Versailles made him famous, fashionable and highly sought-after in the royal courts of Europe.

When Charles II decided to redesign Greenwich Park, then, he ‘begged’ one of his officials to write to Louis XIV, asking for his celebrated gardener’s services.

The French King replied:

Although I have need of Le Nôtre continually […] I will certainly allow him to make the journey to England since the King so desires.

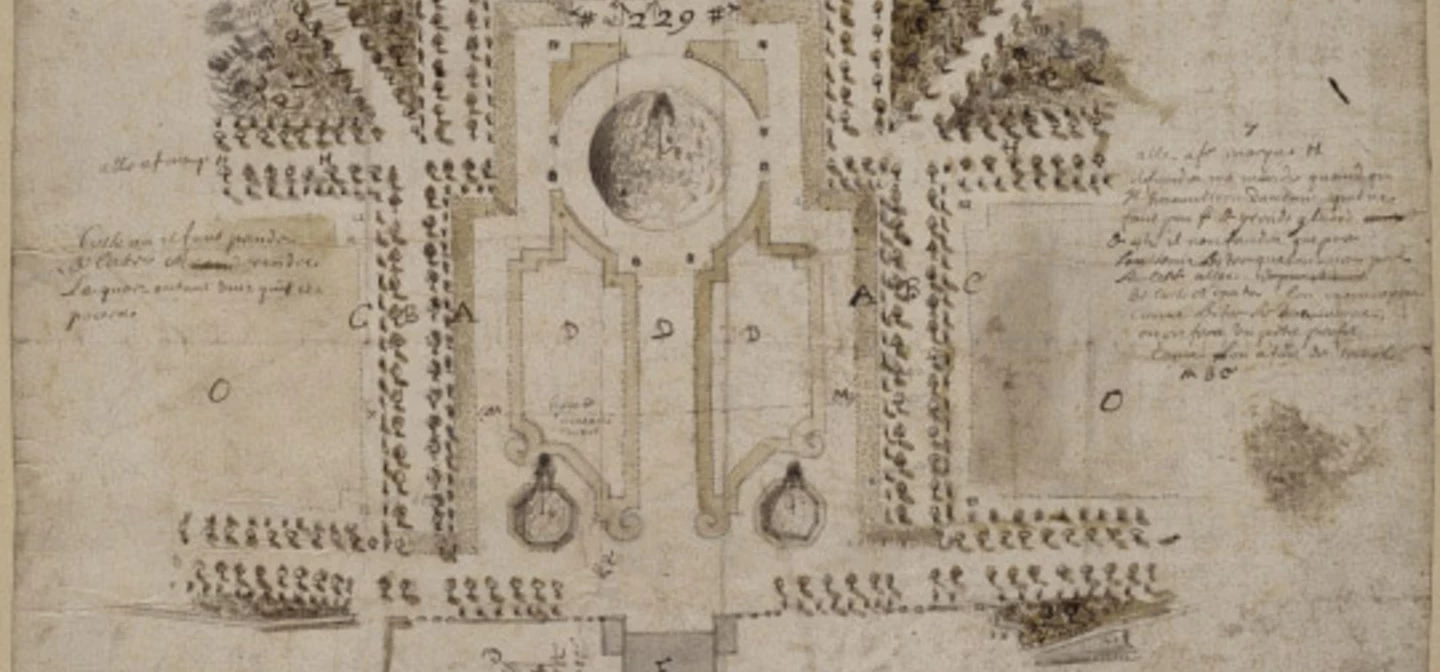

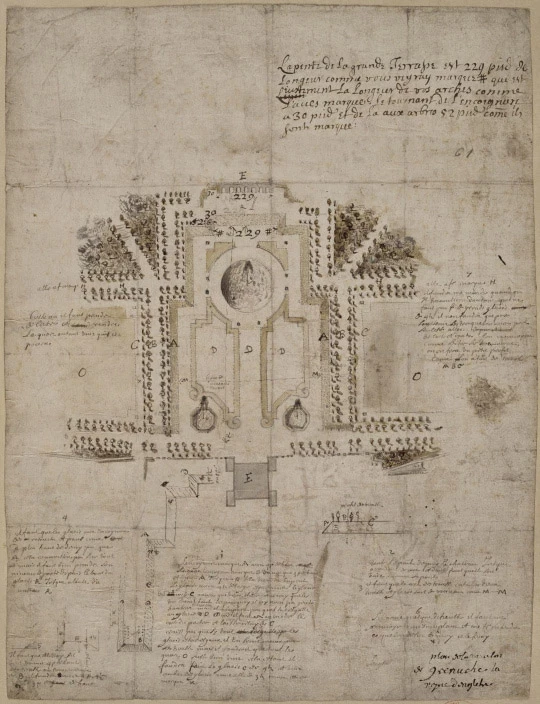

It is unclear whether or not Le Nôtre ever made it to England, but he certainly drew up a plan for Greenwich Park that was rediscovered at a French archive in the 1950s. This shows his scheme for the northern part of the park, sitting between the Queen’s House and the Royal Observatory.

Formal landscaping

Le Nôtre’s plan shows that this layout was framed by symmetrical avenues of trees. These were eventually planted and the plan is still visible today, giving Greenwich Park its unique formal landscape.

Not all of Le Nôtre’s plan came to fruition, though. In the middle of the tree avenues, he had designed a ‘parterre’. This term, which translates as ‘on the ground’, refers to part of a formal garden made up of plants and beds that form a pattern – particularly when viewed from above.

Though the parterres were never completed, Le Nôtre’s planned ‘parterre banks’ were. These are sharp banks that were cut in alongside the eastern and western tree avenues, framing the Queen’s Field – the central expanse of grass at the north end of the park. The outline of these can still be seen in Greenwich Park, though they have been eroded over the centuries and are not as sharp as they once were.

Greenwich Park Landscape Restoration

The Royal Parks is embarking on a momentous 3-year plan to protect and restore Greenwich Park’s threatened 17th century landscape.

A dig with a grand view

Over the past few months, the archaeology team have been working on the Grand Ascent, the slope below the General Wolfe statue.

Greenwich Park

Welcome to Greenwich Park, one of London’s eight Royal Parks; a mix of 17th-century landscape, stunning gardens and a history dating back to Roman times.

Sir William Boreman

Sir William Boreman was a nobleman and philanthropist who also served as Clerk to the Royal Household under Charles II. Surviving records show that he was responsible for implementing key elements of the ambitious ‘Grand Plan’ at Greenwich Park.

The scarcity of surviving records makes it hard to know exactly how Boreman and Le Notre worked together and the extent to which the work of each influenced the other. What we do know is that Boreman was responsible for introducing an iconic feature to the park in 1662: the ’Grand Ascent’.

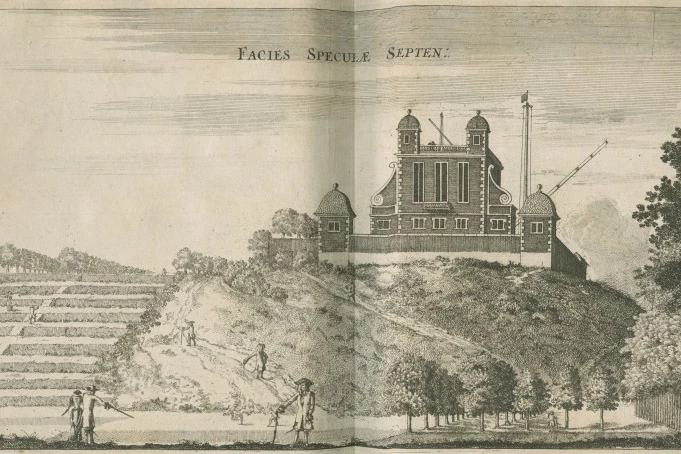

The ‘Grand Ascent’, sometimes called the ‘Giant Steps’, were a series of terraces that were cut into the hill that leads up to the Royal Observatory. They were flanked with Scotch fir trees on either side. Like Le Notre’s parterre banks, the steps have been eroded over time – their outline is only faintly discernible in the park today.

Still in place, though, are some of the seven tree avenues established by Boreman across the park. In 1664, diarist John Evelyn reported that the trees being planted in the park were elms. Over the centuries, these trees have been replenished and replaced – but the layout of the avenues remains.

Pepys’s Perspective

Another well-known diarist left us an important record of the work at Greenwich Park, too. On one of his regular walks in Greenwich Park, Samuel Pepys admired the trees being planted by Charles II.

In his famous diary, Pepys wrote:

walked into the Park, where the King hath planted trees and made steps in the hill up to the Castle, which is very magnificent

Related Articles

-

Read

ReadQueen Elizabeth Oak in Greenwich Park

Greenwich Park boasts thousands of trees, but Queen Elizabeth’s Oak is easily the most famous.

-

Read

ReadGreenwich Park in Art

For centuries, artists have flocked to Greenwich Park armed with sketchbooks, palettes and canvases.

-

Read

ReadFamous Artists at Greenwich Park

Among the thousands of artists who have found inspiration in Greenwich Park are three of the most well-known figures in Western art…